Classroom management provides for us perhaps the greatest of juxtapositions between frustration and comedy. When we take the time to look back on some of our classroom management challenges, the stories come pouring out.

Don’t believe me? Next time you have lunch with a group of colleagues, ask them to share their favorite classroom management stories; you’ll laugh for days. However, in the moment, the mismanaged classroom can easily ruin not just that specific class period, but the entire day and, potentially, an entire year or semester.

We’ve all had that one class that, by November, you dreaded going to because you knew every single minute would be a battle. Of course, there are countless strategies to help deal with classroom management issues, but at its core, combating the chaos rests in understanding and honoring humanity. As you consider some of your most challenging students or classes, think about your approach to classroom management through the lens of these three areas: connection, consistency, and compassion.

VIDEO: New Teacher Survival Guide: Classroom Management

Connection

On the surface, this might seem simple. When we’re connected with our students, two things happen: they want to behave better and when they don’t, it’s easier to manage their behavior. This isn’t a surprise; however, there’s a lot more to using connection as a classroom management technique than just building relationships with students.

The teachers who are most effective at using connection are deliberate in connecting with all stakeholders: parents, deans, athletic coaches, administrators, co-curricular sponsors, counselors, and other teachers. The old adage “it takes a village” rings true when thinking about classroom management. When teachers use their connections to all of these different people and supports, not only can they better manage behavioral issues, but students see just how many adults in the building care about helping them to succeed. I know when I was a head coach, my athletes were always taken aback when I knew specifics of how things (good and bad) were going in their classes. This level of connection only helps everyone be in the know and to collaborate together for the benefit of the student.

Consistency

I firmly believe that this is probably the most obvious, but also the most difficult of the three Cs. It isn’t rocket science that teachers need to be consistent when managing behavior; however, the depths to which this is true extend way beyond the obvious. When we think about consistency with classroom management, for the most part, we gravitate toward thinking about being consistent when handing out consequences, and of course, that’s very important. But the consistency can’t stop there; we must also be sure to be consistent in other ways. We must be deliberate with factors like the tone of our voice to each student, how much time we spend building connections with each student, and more.

This is why I say this one is so hard — because teachers are human and humans inherently connect with certain people more or less than others. We instinctively gravitate to others who are like us and share common interests, and students notice that much more quickly than we realize. I remember a student telling me at the end of one school year,

“I really enjoyed your class, but I wish you didn’t play favorites so much.”

I was taken aback, and I asked the student to expand on why she felt that way. She said,

“Well, you spent a lot of time talking about golf and volleyball with those athletes, but you didn’t really spend much time talking with me about my ice skating.”

She was right; I didn’t — but not because I intentionally didn’t want to. I just love golf and volleyball, and I unconsciously gravitated to those students and those conversations, never giving much thought to the inconsistency. So when we think of being consistent with our classroom management, it has a much greater reach than just being consistent with our consequences. We must work hard to ensure that all aspects of our behavior are consistent; doing so only helps the students see that we care equally about all of them, and only makes managing behavior that much easier.

Compassion

If consistency is the most difficult of the Cs, compassion is the most important. I was recently talking with a coach who was really struggling with an incident that occurred involving his athletes on the bus ride home from a game. He was disturbed at the number of gay slurs in the song that they weren’t only blaring on the speaker, but loudly singing along with. As we discussed how to handle this incident, I could tell he was furious — and I didn’t blame him. But as we worked through it, I kept reminding him of one fact: these are 15-17-year-old kids… if they didn’t make mistakes like this, we wouldn’t need teachers and coaches.

When our students are at their “worst” we must be at our best — teaching and coaching even more. Don’t get me wrong, managing behavior with compassion doesn’t mean we excuse wrongdoing. In fact, it means we must acknowledge the mistakes and use them as avenues for teaching humanity. It also means that we model that same humanity as we manage mistakes, so students don’t leave feeling “bad” or with a deficit in self-worth. They need to know that we care — unconditionally.

As I continued to remind this coach, that while of course we wish this incident didn’t happen, we also have a choice to look at it like this: We can be glad it did happen because it gave us a chance to work with these kids to understand the impact of their actions in a larger context of not just their own lives, but the lives of others as well. If we remember first and foremost that we are teachers of kids and not content, we can bring the highest levels of compassion to our classroom management, even when it’s most challenging to do so.

Ultimately, there is no magic wand when it comes to managing student behavior. In fact, I’ve often said that part of the reason why it can be so difficult is that so many elements of classroom management are unteachable. However, when we work to create a classroom that’s connected, consistent, and filled with compassion, we start to bring out the humanity in the profession and the best of all involved.

For more ideas on classroom management, check out Teaching Channel’s other blog posts on the topic.

This article was originally posted on April 17, 2018. It has been updated with new information and links.

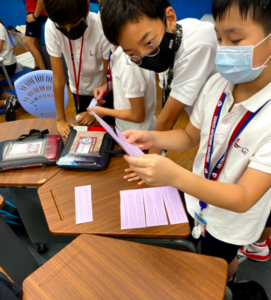

Jigsaw is a cooperative learning strategy that enables each student of a “home” group to specialize in one aspect of a topic (for example, one group studies habitats of rainforest animals, another group studies predators of rainforest animals). Students meet with members from other groups who are assigned the same aspect, and after mastering the material, return to the “home” group and teach the material to their group members. With this strategy, each student in the “home” group serves as a piece of the topic’s puzzle and when they work together as a whole, they create the complete jigsaw puzzle.

Jigsaw is a cooperative learning strategy that enables each student of a “home” group to specialize in one aspect of a topic (for example, one group studies habitats of rainforest animals, another group studies predators of rainforest animals). Students meet with members from other groups who are assigned the same aspect, and after mastering the material, return to the “home” group and teach the material to their group members. With this strategy, each student in the “home” group serves as a piece of the topic’s puzzle and when they work together as a whole, they create the complete jigsaw puzzle. Before reading

Before reading During reading

During reading

As with most art, constraints improve the output: limit the number of words that students can use in a row, or set a minimum or maximum number of words.

As with most art, constraints improve the output: limit the number of words that students can use in a row, or set a minimum or maximum number of words. During our study of world religions, I wanted to ensure students thoughtfully read an article about the Dalai Lama. To get them talking and processing, I spaced

During our study of world religions, I wanted to ensure students thoughtfully read an article about the Dalai Lama. To get them talking and processing, I spaced

Ask students to read an article or watch a video that has two perspectives; we watched the

Ask students to read an article or watch a video that has two perspectives; we watched the